Five hundred years ago, when the Spanish conquerors arrived in what is now Mexico, the region was populated by millions of indigenous inhabitants. The conquistadores characterized them as Aztecs, because they were all united under the expansive Aztec empire.

When the Spanish came to central Mexico in 1519, they were armed with the doctrines and rituals of the Catholic Church, and began the evangelizing process immediately. This meant instituting all the religious holidays that they celebrated in the New World. During the evangelizing process, the Spanish invaders demolished religious temples, burned indigenous idols and destroyed Aztec books. But the indigenous people resisted efforts to eradicate their culture and instead, often blended their own religious and cultural practices with those imposed on them by the Spanish.

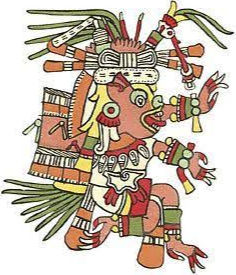

One major festival of the Aztecs was the celebration of the death goddess Mictecacihuatl, who presided over the underworld (Mictal) with her husband. She was celebrated in a month-long, raucous festival, in July and early August.

According to one of the myths, Mictecacihuatl’s job was to watch over the bones of those who had died, which would then be used to create new life on earth. To that end, the common people buried their dead family members under their own houses to keep them close, and laid food and precious objects with the departed to appease these fearsome underworld gods. Once a year, Mictecacihuatl ascended to the land of the living to make sure the bones were being cared for properly. The people celebrated her arrival with dance, food, flowers, singing and dancing, in gratitude for her protection with a dynamic, month-long party. It was a celebration of death, but also a remembrance of those who had passed, showing the never ending connection between death and life.

The Spanish viewed these rituals as sacrilegious, but could not quash the millennial worship and celebration of Mictecacihuatl. The Spanish Catholic Church decided to compromise. They melded the indigenous festivities into a three-day Christian observance, from October 31 through November 2, to coincide with All Saints Day and All Souls Day.

Like many Mexican holidays, the Day of the Dead is an example of syncretism—the melding of rites and traditions of the indigenous people and those of the Spanish conquerors. However, the syncretic blending of Catholic and Aztec beliefs in the celebration of Day of the Dead is built upon earlier mixing of cultures and traditions. It combines the rituals and beliefs of three diverse cultures. Think of an Irish stew with Spanish chorizo, jalapeno peppers, and a generous sprinkling of Catholic blessings.

One part of the story begins in the British Isles, with a 2500-year old Celtic festival named Samhain (pronounced Sow-an).

It was celebrated beginning on the eve of October 31 and continued into November 1; a time of year when “the summer goes to rest.” A pagan, agricultural festival, it defined the separation between summer’s lightness and winter’s darkness, and a time “when the normal order of the universe is suspended.” The Celtic people believed that on this day the veil separating the living and the dead was especially thin, and allowed spirits to visit the living. People prepared the favorite food of a beloved dead, or they might set a place at the table for them. It was a time of prophesies, of disguising oneself to avert evil, of building large bonfires in the hope it would please the gods, and regenerate plants. In ancient times they would circle the bonfire with the skulls of their ancestors, representing communion with the dead.

For Christians, on the other hand, starting in the 4th century, there existed in certain places and at sporadic intervals a feast day to commemorate all Christian martyrs. By the early 7th century the Sunday after Pentecost was a commemoration of all saints, martyred or not. In 609, May 13 was chosen because it coincided with the date of the Roman pagan festival of Lemuria (another example of syncretism), in which malevolent and restless spirits of the dead were propitiated. By 800, the churches in the British Isles were holding a feast commemorating all saints on November 1; this, most likely to absorb the pagan feast of Samhain into Catholic doctrine. The November 1, All Saints Day was made a day of obligation by papal decree throughout the Holy Roman Empire in 835. November 2 was added in the 10th century, becoming All Souls Day. It is the official time to visit cemeteries to pay respect to those who need to be purged of their minor sins.

The latest addition to the Day of the Dead celebrations is the transformation of the primordial Mictecacihuatl into a new “lady of death.” The skeleton woman wears fancy clothes and a European hat adorned with flowers and feathers, appeared in 1913 as a cartoon character created by Mexican printmaker and lithographer Jose Guadalupe Posada. His intent was to poke fun at the wealthy social types who tried to be more European in their dress, denying their indigenous heritage. He believed death was democratic and in the end, we all end up as skeletons no matter what our status in life. But he did not give her a name; that was up to Diego Rivera who called her Catrina and immortalized her in his grand mural in Mexico City, titled Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda. Below, she stands with Frida Kahlo to her right.

The historical period was the Porfiriato, the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz who had an overwrought admiration for anything French. In the mural he is in the right upper hand corner, a mustachioed white haired man, with an elegant dress chapeau. It was during his 35-year presidential term, 1877 to 1911, that French aesthetic influenced architecture and other aspects in Mexico. Diaz set out to turn Mexico City into a mini-Paris with French-style parks and boulevards, construction of major government and civil buildings following the style of European royalty, and monumental statues at major intersections. These styles filtered to other cities in Mexico where today we see such architecture from the period and many parks that mimic French design, with wrought iron benches, manicured paths, and a central gazebo. In San Miguel we have Parque Juarez which was created during the Porfiriato, and shows all those elements.

But the beautification of cities was not enough to mitigate the negative effects of the Porfiriato—the suppression of human rights, and a government benefiting the army, foreign capitalist, large landowners, and the Catholic Church. All this, ignoring the needs of the poor, the peasants, and the general population; it was a period of a dictatorship dedicated to the wealthy, and it led to the ousting of Diaz in 1910, and the Mexican Revolution. However, the Catrina, born during his term in office remained, and became more significant that ever during the celebrations of the dead.

Today, in Mexico, Dia de los Muertos—Day of the Dead—is one of the biggest national celebrations, where the line between Catholic dogma and pagan rituals become blurred. The festivities bring back many of the traditional elements from the diverse cultures that have influenced the celebration of Dia de los Muertos.

Many of the rituals harken back to the pagan beliefs about the propitiousness of this day to communicate with the dead. On that day, Mexicans build private altars for their dead in which they place favorite foods, beverages, and photos of the departed, all with the hope the souls will visit.

Calaveras (skulls) and calacas (skeletons) are used as symbols, which celebrants show on masks or costumes. Sugar and chocolate are traditional food staples, and sugar, in particular is used to create skulls, which can be given as gifts to both the living and the dead. There is also pan de muerto (bread for the dead), a sweet egg bread in many shapes, and there is an overwhelming use of flowers, particularly marigolds, to decorate the altars. These, you will recall, connect back to the ancient Celtic traditions of preparing the favorite food of the departed, and to the Aztec veneration of Mictecacihuatl with breads and flowers. This year, when you watch the celebration, know that you are looking at almost three millennia of traditions on two continents.

Comments